Fred Hirsch spent 60 years engaging in tireless work as an activist with Local 393, the South Bay Labor Council, the United Farm Workers, and countless local and global struggles. Regardless of how you crossed paths with Fred, he undoubtedly pushed you to be better and do more. He was an unyielding force for justice, not for a narrow group of people locally, but nationally and internationally to do right by all human beings and improve the lives of working people everywhere.

Fred was a skilled mechanic – a great plumber. He worked hard every day and raised the craftsmanship of people around him. At break time, he would talk about the union. Then he’d go home, where there’d be a constant flow of guests from the movement: farm workers, Black Panthers, and anti-war demonstrators. They would talk, argue, and strategize, create activist literature on his garage printing press, and assemble picket signs for the week’s demonstrations.

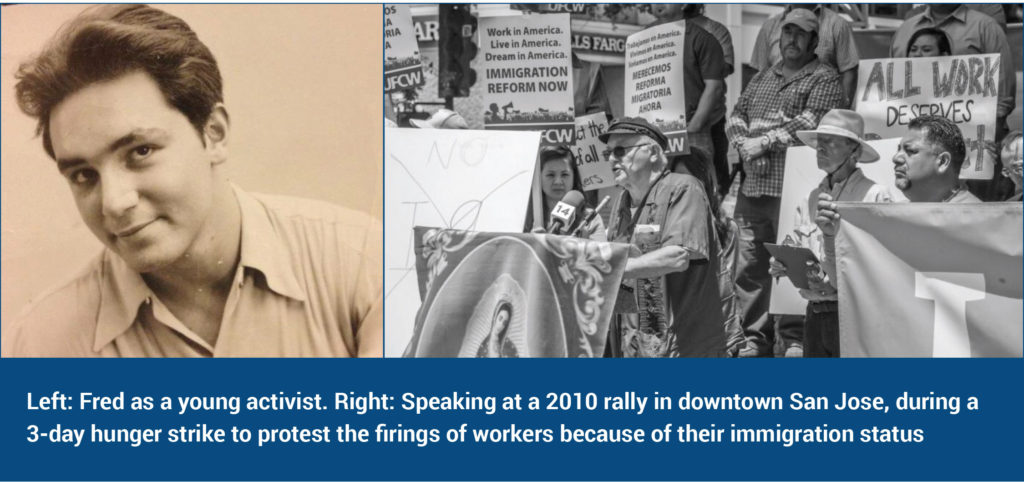

At his memorial, Fred’s children, friends, and colleagues recalled his steadfast presence and leadership at rallies, marches, and picket lines. Afterward, they’d break bread, debrief, and plan for the next action without a moment’s rest.

Activism was Fred’s life, and justice was in his blood. Doing nothing, doing something half way, or doing something without complete integrity was not acceptable. He could not be a silent witness to injustice. So even when something wasn’t right within our own ranks in the labor movement, Fred would be the first to call it out.

Part of what made Fred’s leadership so visionary and ahead of his time was that he saw the interconnectedness of all people’s struggles. Whether it was workers building Silicon Valley’s tech campuses, Black youth in the city, immigrant farmworkers in the fields, or the casualties of war in Latin America, Fred would make those connections, and make sure everyone around him did too.

In Fred’s final years, he battled illness, sidelining his activism. He couldn’t remember there was a pandemic, but he always remembered our monthly union meetings. The 393 union hall was closed, but his partner, Martha, would drive him past the building to satisfy that itch. Hopefully, that itch for union camaraderie, activism, and justice can live on in all of us. Fred would have wanted it that way – in fact, he would have insisted on it…

Fred Hirsch’s grandson, Sascha Dubrul, described him as a “badass internationalist, anti-racist, and anti-fascist.” Sascha recounted Fred’s words describing his own life and unyielding dedication to activism.

“Most of what I have I done has kept me from being an adequate father when my daughters were young. It has made me a somewhat distracted lover when I should have shown my love. It has kept me from going fishing and rocking around on the sea as a good man should. It has distracted me from writing the great novel of our time. It has kept me from taking the political mantle where I might use the public megaphone of the city council, county board of supervisors, or state legislature…It has kept me from working on my trade full time, making a good living, and feathering my nest. But all in all, I probably have done what I do best. I am happy and have done what I might to fight the good fight and generate a good network of working class love, power, and light.”

– Fred Hirsch

Fred Hirsch & May Day

The following is an excerpt from David Bacon’s article “Doing the Work that Needed to be Done,” which was published in OrgUp’s blog. Bacon is a writer, photographer, a former factory worker, union organizer, and immigrant rights activist.

When Adriana Garcia heard about his death, it was a blow. “The whole South Bay is hurting,” she mourned. Garcia heads MAIZ, a militant organization of Latina women in Silicon Valley. For many years she and Fred co-chaired the annual May Day march from San Jose’s eastside barrio to City Hall downtown.

The recovery of May Day was one of the great political changes that took place during Fred’s lifetime. May Day commemorates the great demonstrations in Chicago in 1886 for the eight-hour day, and the execution of the Haymarket martyrs a year later for leading them.

When Fred became a political activist and Communist in the 1950s, the holiday had become virtually illegal, a victim of Cold War hysteria. It was called the “Communist holiday,” celebrated everywhere in the world but here.

Fred grew up in New York, where police on horseback attacked the May Day rally in the city’s Union Square in 1952. They clubbed down mothers with strollers who were holding signs calling for justice for Willie McGee, a victim of legal lynching in Mississippi.

Years later it was no surprise that Fred helped organize a local support network for the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee. SNCC fought the racism and political repression in the South that killed McGee, and its courageous student activists helped end the dark years of McCarthyism.

Even by the 1970s, fear of redbaiting still kept most delegates away from the May Day events Fred would organize among delegates to the Santa Clara County (now South Bay) Labor Council.

In 2006, though, everything changed. Millions of immigrants chose May Day, a holiday they knew well from back home, to pour into the streets, protesting a law that would have made it a felony to lack immigration papers. Tens of thousands marched in San Jose. In the years that followed, when Fred and Adriana asked unions to come out for May Day, they’d bring banners and arrive by the busload.

To Fred, May Day wasn’t merely a radical symbol. It was a chance to connect union and community activists in San Jose to people far beyond the country’s borders, and to talk about a shared set of politics. Making those connections, seeing the world joined by the bonds of a common class struggle, was the thread that ran through Fred’s politics throughout his life.

In the outpouring of messages from activists hearing of his death, it was apparent that plenty of people had absorbed Fred’s ideas. Virginia Rodriguez, the daughter of farmworkers and a lifetime labor organizer like him, passed away before he did. But she shared his confidence in a vision of an ongoing core of politically committed activists.

“I came to believe,” she said, “that there will always be those individuals who will respond to the outer edges of what needs to be done, and who will step forward to take up responsibility for what is called for if change is to take place. In so doing, these people help move others to come along. It underscores the principle that if enough of us carry out a piece of what needs to be done, then change will most certainly come.”